Conclusion

The Triumph of the Private

In many ways, the nineteenth century saw the establishment of a private America. The rise of the market economy prompted the simultaneous rise of a private middle-class culture. The middle class established the home as genteel and removed from the marketplace, and then having created a private world, imbued it with special force. The private person -- moral, respectable -- was the real person.

But how to identify that private person? The social and physical mobility that came with the market meant that many Americans of the mid-nineteenth century met people who were not familiar, who could not be identified as safe or dangerous. Science provided an answer, locating the essential nature, the private nature of a person, in the physical: in the shape of the head, the angles of the face, and the color of the skin.

The daguerreotype arrived in the United States at a perfect moment, in a sense. Society demanded a look at the inner, private essence of a person; the haunting reality of the photograph seemed to provide just that. The essence of a person was located in his or her physical attributes; the daguerreotype provided an careful (indeed, unquestionable) record of those attributes.

The triumph of the private man even pushed its way into the public realm. A wave of nationalistic fervor in the early and mid-nineteenth century produced a pantheon of public heroes -- icons who were loved as public and as private men. The central figure in this movement was George Washington. The worship of Washington was both exploited and fed by Mason L. Weems, author of The Life of Washington and the source of many of the still-living myths about Washington's childhood, including the story of young George chopping down a cherry tree and the tale of his throwing a stone across the Rappahannock. Weems' stories were borrowed shamelessly by other biographers of Washington, the most popular being the cherry tree story, which made its way into the widely read McGuffey's Reader.Marcus Cunliffe, ed., Mason L. Weems, The Life of Washington (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1962), Introduction, pp. xiii-xxi.

Weems' book was so popular because it satisfied two requirements of the public need: to understand the real Washington, the private Washington conveyed by stories of childhood, and to maintain his God-like aura. "It is not in the glare of public, but in the shade of private life, that we are to look for the man," he wrote.

Private life is always real life. Behind the curtain, where the eyes of the million are not upon him, and where a man can have no motive but inclination, no excitement but honest nature, there he will always be sure to act himself; consequently, if he acts greatly, he must be great indeed. Hence it has been justly said, that, "our private deeds, if noble, are the noblest of our lives."Weems, Life, p. 2. Italics are Weems'.

Washington, of course, was not the only American hero, though he was the most revered. A pantheon of public figures -- senators, judges, generals, artists, writers -- emerged, satisfying the public need for leaders and heroes, and presented both as great public men and virtuous private citizens. The aura of these heroes was spread largely, in the 1840's and 1850's, by displays of daguerreotypes in the urban studios.

While the profits at Matthew Brady and Southworth and Hawes's studios were made through private portraits, they attracted those customers with a varied and changing gallery of public figures. "People used to stroll in there in those days," a Harper's Magazine writer wrote in 1863, "to see what new celebrity had been added to the little collection, and the last new portrait at Brady's was a standing topic of conversation." The photographs of the famous were a necessary element, and object of pride, of the studio, and they were why many patrons came. Trachtenberg, Reading, p. 39.

The public daguerreotype operated on principles comparable to Weems'. Weems created a sense that he was delving into Washington's private life, then created a fictional one. The public daguerreotype, with its reputation for probing accuracy, seemed to be showing "honest nature," and with its parlor props, claimed to be showing the public figure in a private moment.

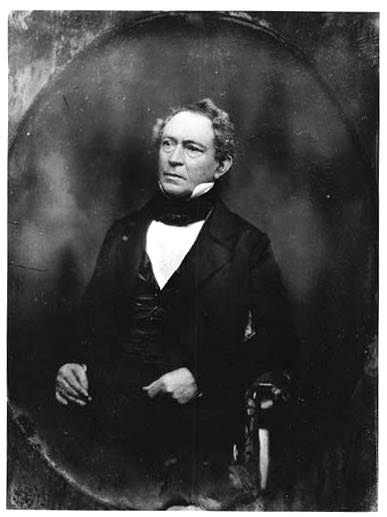

The conventions of the public daguerreotype maintained a careful line between familiarity and disrespectful intimacy. The Southworth and Hawes photograph of Edward Everett, the minister, Governor (of Massachusetts), Senator, and orator who is now best known for speaking before Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, shown above, is typical. Everett is sitting in a parlor armchair, giving the impression that we are looking into his comfortable parlor, into his private life, and his expression is thoughtful but relaxed. He is not looking directly as the camera, as many private subjects did, but off to the side, as was customary in public daguerreotypes. Alan Trachtenberg notes that "an intimate gaze into the eyes of the viewer [would] be unseemly."Tractenberg, Reading, p. 46. The fact that such a complication was even an issue is significant. The daguerreotype, as we have noted, created presence; as the subject peered outward, so the viewer peered in, close, intimate -- crossing the boundary into a public man's private life.

In age of inventions that transformed the public world -- the telegraph, the steamship, and the railroad, for example -- the daguerreotype, small and meaningless to a stranger, was a domestic invention. It made all that it touched domestic and private, even the great men of the age, and it recorded, celebrated, and solidified the conventions of a private middle-class world.

One of the unspoken themes of this paper has been the relationship of the daguerreotype to our own time. Many habits and images that seem eternal to us -- the middle-class notions of home, work, and manners, the meaning of the posed photograph, the relationship of an image to a life -- flow from the world of the daguerreotype. The daguerreotype was intertwined with the attitudes of the private world of the nineteenth century, and when we peer into it, some of those feelings, mingling with our own reflection on the silvered surface, slide into focus.